Nanette Wylde has a nice interview with Pod Post (Jennie Hinchcliff and Carolee Gilligan Wheeler) on her blog Whirligig. (Pod Post wrote the book Good Mail Day and sell merit badges for letterpress and the book arts.)

Nanette Wylde has a nice interview with Pod Post (Jennie Hinchcliff and Carolee Gilligan Wheeler) on her blog Whirligig. (Pod Post wrote the book Good Mail Day and sell merit badges for letterpress and the book arts.)

Nanette Wylde has a nice interview with Pod Post (Jennie Hinchcliff and Carolee Gilligan Wheeler) on her blog Whirligig. (Pod Post wrote the book Good Mail Day and sell merit badges for letterpress and the book arts.)

Nanette Wylde has a nice interview with Pod Post (Jennie Hinchcliff and Carolee Gilligan Wheeler) on her blog Whirligig. (Pod Post wrote the book Good Mail Day and sell merit badges for letterpress and the book arts.)

Recently I realized that my most creative periods have coincided with my practice of writing haiku (or really senryu) regularly. My first artist’s book was called Haiku, my calendars used my haiku as did my most recent artist’s book Walking. But for the past year, I’ve only written a handful of them. I’ve tried various strategies to get myself writing again, and because I think blog posts should be pretty short, I’ll write about them over the next couple of weeks.

![]() What seems to have worked this week is reading Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop. (I’m reading books set in New Mexico, since we just moved there.) Cather’s vivid landscape descriptions are perfect inspiration for haiku.

What seems to have worked this week is reading Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop. (I’m reading books set in New Mexico, since we just moved there.) Cather’s vivid landscape descriptions are perfect inspiration for haiku.

![]() The picture below is from my family room window after a snow storm early last week. And yesterday we had a thunderstorm with lightening and snow. Here’s my reaction:

The picture below is from my family room window after a snow storm early last week. And yesterday we had a thunderstorm with lightening and snow. Here’s my reaction:

The sky grows dark

With a clap of thunder and jolt of lightening—

My computer screen flickers off.

We’ve been in Santa Fe about 6 weeks now, and I’m getting lost (or at least turned around) less and less every day. In giving directions to our place over the phone, we’ve found the biggest issue is the pronunciation of the street names — how do you say, for instance, “Callecita”? The “ll” is pronounced “y” by some, and “ll” by others. The other one is “Cordova”—is the second “o” a long “o” sound or a sort of “u” sound, is the first syllable stressed or the second? (Answer: stress the first syllable, pronounce the second “o” as the “u” in “must.”)

We’ve been in Santa Fe about 6 weeks now, and I’m getting lost (or at least turned around) less and less every day. In giving directions to our place over the phone, we’ve found the biggest issue is the pronunciation of the street names — how do you say, for instance, “Callecita”? The “ll” is pronounced “y” by some, and “ll” by others. The other one is “Cordova”—is the second “o” a long “o” sound or a sort of “u” sound, is the first syllable stressed or the second? (Answer: stress the first syllable, pronounce the second “o” as the “u” in “must.”)

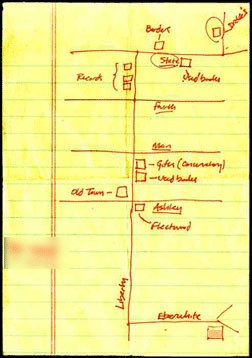

![]() Over on Slate there’s been a series on signs, subtitled “how they tell us where to go.” Recently there was a post entitled Do You Draw Good Maps?, about Paul Stiff, a reader in typography and graphic communication at the University of Reading in the United Kingdom, and who’s been looking at hand-drawn maps for three decades. (Like the one to the left.)

Over on Slate there’s been a series on signs, subtitled “how they tell us where to go.” Recently there was a post entitled Do You Draw Good Maps?, about Paul Stiff, a reader in typography and graphic communication at the University of Reading in the United Kingdom, and who’s been looking at hand-drawn maps for three decades. (Like the one to the left.)

Stiff believes that we amateurs have something to teach the pros. Our maps are efficient—they edit out unnecessary information. They often include what Stiff calls “an error detector, something that tells you something’s gone wrong.” (If you see the red barn, you’ve gone too far.) They adhere not to mapmaking norms but to the user’s particular needs.

Check out the post here, as well as the rest of the series.

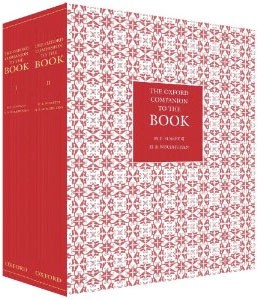

About The Oxford Companion to the Book, this review says “This colossal new encyclopaedic Companion has something to say about almost everything that matters in the world of writing, printing, publishing and book-collecting….not just the history of print, but also the history of manuscripts, libraries, bookselling and book-editing. Dozens of experts have contributed, submitting long essays on general topics or short reference entries. The result is an extraordinary tour de force, a cornucopia of bookish information.” It’s 2 volumes, 1048 pages and costs over $250 on Amazon. You can read excerpts here.

About The Oxford Companion to the Book, this review says “This colossal new encyclopaedic Companion has something to say about almost everything that matters in the world of writing, printing, publishing and book-collecting….not just the history of print, but also the history of manuscripts, libraries, bookselling and book-editing. Dozens of experts have contributed, submitting long essays on general topics or short reference entries. The result is an extraordinary tour de force, a cornucopia of bookish information.” It’s 2 volumes, 1048 pages and costs over $250 on Amazon. You can read excerpts here.

When we bought our place in Santa Fe, the selling realtor told us a vague story of a lawsuit concerning the development of the large piece of property next to ours. I was reminded of this the other day, and I spent a bit of time with Google trying to find out more information. I found the judgment quickly, but the legal jargon was awfully confounding. What’s a “protectable property interest?” All I came up with at first were more judgments and yet more lawyer-ese. By changing “protectable” to “protected” I think I was able to figure it out.

When we bought our place in Santa Fe, the selling realtor told us a vague story of a lawsuit concerning the development of the large piece of property next to ours. I was reminded of this the other day, and I spent a bit of time with Google trying to find out more information. I found the judgment quickly, but the legal jargon was awfully confounding. What’s a “protectable property interest?” All I came up with at first were more judgments and yet more lawyer-ese. By changing “protectable” to “protected” I think I was able to figure it out.

![]() As I told the story of the lawsuit and my frustration with the words to my husband over dinner, I asked aloud whether I just needed to work on my vocabulary. Last year I noticed that I used the generic word “funny” when I really wanted to use something more specific — like “ironic” or “absurd” or “clever” or “risible” or “odd” or … With what seems like a lot of concentration, I’m making some headway with that.

As I told the story of the lawsuit and my frustration with the words to my husband over dinner, I asked aloud whether I just needed to work on my vocabulary. Last year I noticed that I used the generic word “funny” when I really wanted to use something more specific — like “ironic” or “absurd” or “clever” or “risible” or “odd” or … With what seems like a lot of concentration, I’m making some headway with that.

![]() Then, on Sunday, in the On Language column of the NY Times Sunday Magazine, Ammon Shea writes about whether worrying about one’s vocabulary size is worth the trouble. He says

Then, on Sunday, in the On Language column of the NY Times Sunday Magazine, Ammon Shea writes about whether worrying about one’s vocabulary size is worth the trouble. He says

There are thousands of books and Web sites, many of them quite commercially successful, that promise to help redress the problem. The cover of the audio book Wordmaster exhorts you to “Improve your word power and improve your life!” The Web site Verbalsuccess.com avers that its method will earn you greater respect in life and allow you to make more money after using it for just a week. Others make promises of a more modest nature, like the cautious claim in the book The Words You Should Know to Sound Smart that it is “possible” that learning its words “may even put some money in your pocket.”

But I loved the title of another book he mentions, The Yo Momma Vocabulary Builder. Shea ends his essay with this thought, which made me remember why I loved words in the first place:

the contemporary book that gives perhaps the most romantic explanation for why you should learn words is The Yo Momma Vocabulary Builder, which says that the “primary reason to seek a larger vocabulary has nothing to do with impressing people, cultivating professional gain or building scholarly achievement.” The reason the authors of this curious book give for learning new words? “It makes life more interesting.”

Read Shea’s entire essay here.