|

Curator's Statement

Livros do Cordel: the street literature of Brazil

By Alastair Johnston, curator

In December 2000, I flew to Salvador de Bahia for a three-month stay, motivated to learn Portuguese, but also to search for copies of the famous livros do cordel, the printed folk literature of northeastern Brazil that we celebrate in this exhibition. After enquiring at several news stands on the praça outside the Mercado Modelo, I found one that had some of the livros. The vendor seemed surprised at my interest, perhaps because the cordel tradition is widely said to be dying out.

Livros do cordel are the last remnants of a balladry tradition that has printed roots back in the 17th century cities of southern Europe. One can also trace connections to troubadour poetry, a literary tradition that predates even the introduction of printing in Europe in the mid-15th century. It was the way news traveled in a pre-literate culture, and vestiges of this can still be found today in West African pop music, and in the corridos of Mexico and other Latin American countries, taking history and current events, as much as romance, as their theme.

Consistent with this tradition, cordel stories concern fate, religion, romance or historic events. Current events, too, get their share of attention, from Minelvino Francisco Silva’s A Moda da Minisaia e a Garota Braza Viva, celebrating the miniskirt, to Pelé na Copa do Mundo e o Brasil Tricampeão, by Severino Amorim Ferreira, which venerates Pelé and the thrice world-champion Brazilian soccer team of the 1970’s. The Pope’s visit or a scandal in government get as much attention from the cordelistas as from the daily press.

At the beginning of the 17th century, a French printer, Nicolas Oudot of Troyes, produced the first livrets des colportages (hawkers’ chapbooks), cheap pamphlets with blue covers by anonymous or Þctitious authors, that sold for two sous. By 1723 there were 150 printers in northern France producing these cheap tracts. Though predominantly religious, the tracts also concerned prophecies, astronomy, miracles, prodigies, medicinal herbs, love secrets, humor, chivalry, etc. Those I have read are not in rhyme. Similar prose pamphlets appeared in England (chapbooks), Germany (ßiegenden blätter), Spain (pliegos suletos) and Portugal (folhas volantes), attaining their greatest popularity in the 18th century.

Beginning in the late 19th century, the Þrst Brazilian cordels were the productions of popular poets like Leandro Gomes de Barros and João Martins de Atahyde (who specialized in supernatural tales, like that of the student who sells his soul to the devil), which were written to be sung to guitar accompaniment. Between 1865 and 1918, an estimated one million cordels were printed in Brazil.

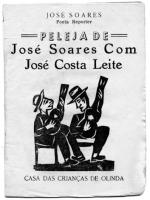

Despite predictions of its demise, there are determined efforts to keep the cordel tradition alive. In the 1970’s the Casa das Crianças de Olinda (a city in Pernambuco, northeastern Brazil) produced 400 titles which were freely distributed throughout the country, some of them reprints of famous historic cordels. The Casa das Crianças (Children’s Home) commissions poetry, as well as artists to provide wood and linoleum cuts for the covers. The Children’s Home hopes to vitiate the blight caused by urban life on poor families by training the youth in traditional local arts.

"One of these traditions is the cordel," says Giuseppe Baccaro, founder of the Children’s Home, "which is embraced by the general public. The cordel is so respected as an art form because of its ability to combine the delivery of information, even tragic news, with the appealing rhythms of the poems and music, performed by the highly regarded repentistas, the poets who sing the poems. The musical variations of the stanzas help to smooth the process of memorization, a proÞciency associated with the poets."

The making of the Livros

The pamphlets are mostly letterpress printed from Linotype slugs on newsprint, roughly 4 1/4 x 6 inches (11 x 16 cm), eight pages in self-wraps, with a single staple in the side. Sometimes a larger sheet has been printed and folded down into quarto to make the eight pages, and is issued uncut. The contents are usually unvarying: six-line verses (sextilhas) with the rhyme-scheme ABCBDB. The metrical feet vary between seven and ten syllables, so, in performance, the poet must add pauses and elide or stretch vowels to make it scan. The monotony of the meter ÿ—ÿ—ÿ—ÿ— ("the boy stood on the burning deck") makes it easy for the poems to fall into the doggerel trap. However, the rhyme scheme and structure are mnemonic devices that help the avid reader, or even the poet, remember how the poem goes.

The covers of these little folhetos are illustrated with zinc cuts of the subject (though sometimes there’s no apparent connection to the contents), with wood- or linocuts. Several of the pamphlets had names and addresses of printers in the vicinity. But though the pamphlets were only a few years old, most of the old letterpress print shops had vanished. The poets too, as far as I could ascertain, were a waning breed, even in smaller towns. They were victims of electriÞcation: rap and hip-hop music supplanted them — you get a lot more attention with a guitar or a beat box backing up your rhymes. "Think bluegrass meets rap," a Brazilian musician advised me. In addition, Brazilian poets have found that internet home pages are a good form of self-publication.

|